Coronavirus an ‘existential threat’ to Africa and her crowded slums

The head of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) has warned coronavirus poses “an existential threat to our continent”. Evidence from past crises shows not everyone is affected equally; the most vulnerable people invariably suffer the worst. This threat will strike worst at the 53 million-or-so people living in the thousands of dense informal settlements, or slums, that pack sub-Saharan Africa’s fast-growing cities.

The risk is particularly high in slums because of the combination of poverty and poor planning.

Poverty leads to fewer choices – do you spend your money on food or medicine? – and few safety nets. Poor planning, if any, has led to millions of people living in largely neglected overcrowded settlements. Their houses are built of waste materials, with little or no running water, electricity, garbage disposal or sanitation.

“Social distancing” is next to impossible when a settlement can have just 380 toilets for 20,000 people. Even before pandemics strike, such places erode the health of residents, causing and worsening ailments that include respiratory diseases.

The call from the United Nations is for rich countries to provide more funding for Africa. But rich donor countries are themselves fighting the crisis and are unlikely to focus their attention elsewhere.

This leaves Africa in desperate need of resources. For example, Central African Republic, home to nearly 5 million people, has just three ventilators.

A history of deadly crises

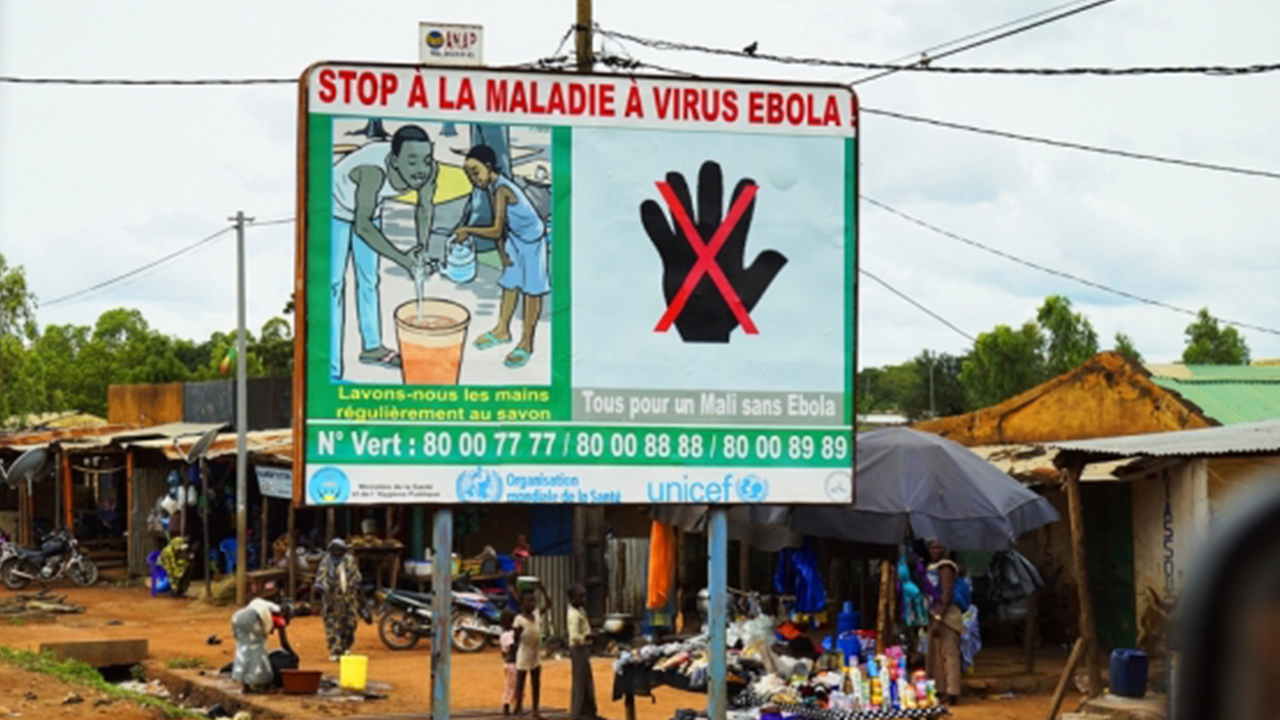

Tragically, Africa is no stranger to crises, including pandemics. In 2014 Ebola swept through West Africa, killing more than 11,000 people.

Lessons emerged from this experience. One was the power of rumour and misinformation – especially in dense urban neighbourhoods. For instance, it was said that Ebola always kills. The claim created panic and led to households hiding sick relatives, resulting in fewer reported cases.

The explosion of social media use – even since 2014 – increases this risk.

In 2018, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) recorded its tenth outbreak of Ebola in 40 years. The outbreak affected the regional capital Goma, a city that is no stranger to crises, having experienced disaster, conflict and a huge refugee influx.

In 1994 hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the Rwandan genocide arrived in Goma. A cholera epidemic that killed nearly 12,000 people followed. Goma endured years of civil war (along with the rest of the country) and a volcanic eruption in 2002.

Now the city is facing coronavirus, having recorded its first case in March. A recent Los Angeles Times article notes that, while chronically under-resourced, Goma’s recent previous experience may help the city fight coronavirus:

Due to the Ebola crisis, the city is dotted with checkpoints where everybody is subjected to a temperature check – performed with handheld infrared thermometers – and required to wash their hands at chlorinated water stations before being allowed to pass.

A testing laboratory is also being built.

This is something, but such measures are likely to have limited impact in slums.

Predictions of disaster ignored

A decade ago, a World Health Organisation bulletin drew attention to a 2009 study that warned Africa’s urbanisation “is a health hazard for certain vulnerable populations … [that] threatens to create a humanitarian disaster”.

Africa has urbanised substantially in the last 11 years. And its slums have grown at break-neck speed. Africa’s population, now 1.1 billion people, is expected to double by 2050, with up to 80% of that increase in cities, especially in slums.

The coronavirus, whose risk to life and economic impacts threaten to eclipse previous crises, threatens to expose the mismanagement and neglect of Africa’s urbanisation in the most visceral of ways. And the most vulnerable people will pay the highest price, as they always do.![]()

David Sanderson, Professor and Inaugural Judith Neilson Chair in Architecture, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.