An underwater quest to restore our endangered seagrass meadows

Potentially, the only way to future-proof Posidonia australis will be to intervene and to combine restoration with some assisted evolution approaches, to give the species the best chance to survive in a world that is changing very, very fast.

A beautiful seagrass is endangered in parts of NSW, but a team of “underwater gardeners” led by a UNSW marine ecologist is working to stem its decline.

Posidonia might sound like a mysterious underwater being in a superhero movie, but it’s real and is fast disappearing from our waters.

Its nemesis is the traditional block-and-chain boat mooring which scars the sea floor as the winds and currents change, creating a halo of destruction.

“Posidonia australis is a slow-growing seagrass that likes to live in the same beautiful sheltered bays where us humans like to live, build our houses and moor our boats, so the building of marinas, coastal development, pollution and dredging has caused its decline,” UNSW marine ecologist Associate Professor Adriana Vergés said.

“Posidonia is a foundation species which provides habitat and food for lots of different animals; it’s also known as a nursery habitat which supports many juvenile species essential for fisheries to thrive.

“Without seagrasses, a lot of emblematic species like seahorses, as well as many species we like to eat, such as blue swimmer crabs, cuttlefish and snapper, would decline from our estuaries.”

Some people might mistake seagrass for seaweed, but it’s a plant just like those on land with seeds, flowers and roots.

Posidonia is also important for carbon capture and storage: the seagrass, when healthy, can store more than 30 times more carbon than rainforests.

“Unfortunately, Posidonia is officially endangered – it’s disappearing from six estuaries in NSW and unless we do something about it, it will be extinct from places like Sydney Harbour in the next 15 years,” A/Prof Vergés said.

Restoring underwater forests

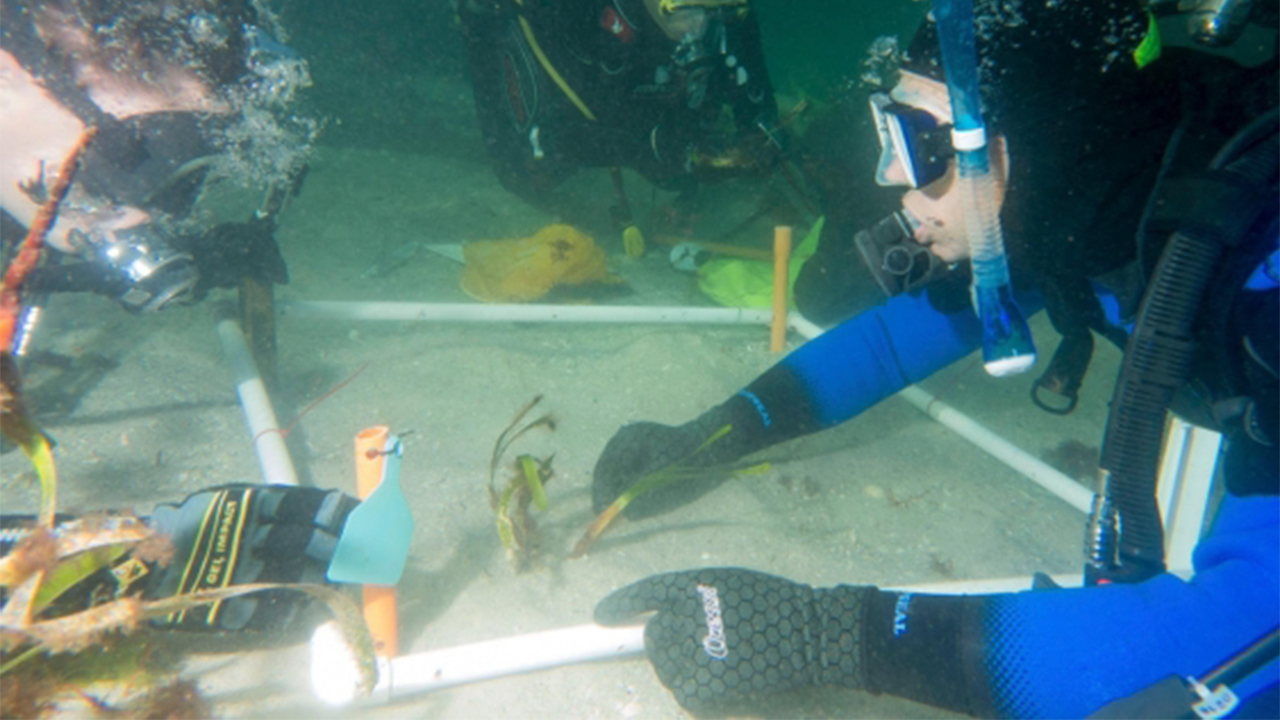

A/Prof Vergés is leading a team of scientists who are passionate about taking action against this problem: Operation Posidonia aims to restore seagrass to estuaries where it is endangered, in conjunction with replacing traditional swing moorings with environmentally friendly ones, also known as EFMs.

The project is a collaboration between UNSW Sydney, the Sydney Institute of Marine Sciences, the NSW Department of Primary Industries – Fisheries and The University of Western Australia.

Only 18 months after its launch, the project is yielding positive results in Port Stephens where a trial is underway with help from community volunteers.

Operation Posidonia’s “Storm Squad” has already collected more than 1500 Posidonia shoots at Port Stephens.

Storms naturally detach Posidonia from the sea floor and the shoots wash ashore.

The volunteers pick up the shoots which are still living and store them at submerged stations for the project’s “underwater gardeners” – the scientists – to take and replant.

A/Prof Vergés said Port Stephens was the ideal test site because there were enough naturally detached shoots for volunteers to collect and the replanted Posidonia had the best chance of survival.

This location is also where NSW Fisheries has a strong base, with huge tanks to store the seagrass shoots between collection and restoration.

The scientists use jute mats to stabilise sediment in old mooring scars, which helps with the replanting of Posidonia. About 70 per cent of the first shoots planted survived.

“Now, nine months after the initial restoration we're starting to see growth from the shoots that we planted; we’ve even seen flowers so it's encouraging,” she said.

“Having said this, every estuary is going to be a bit different. For example, Sydney Harbour is going to be tough to restore, because there's very, very little Posidonia left and there are multiple stressors like boats and ferries.

“So, it's likely that we will be more successful in some estuaries and less successful in others, but where there’s a will there’s a way.”

The NSW Department of Primary Industries pioneered the method of replanting storm-detached seagrass fragments in Australia, inspired by a technique used in the Mediterranean to restore Posidonia oceanica.

This week, from Wednesday 20 November to Friday 22 November, Operation Posidonia’s scientists will don their SCUBA gear and replant the first shoots around the new EFMs at Port Stephens, recently installed into the scars left by traditional block-and-chain moorings.

The next stage is to roll out the project in an endangered estuary.

A/Prof Vergés is drafting grant applications to raise funds to take the project to Lake Macquarie, but she said scaling up the project to restore the seagrass to all six endangered estuaries was at least a decade away.

How you can help

A/Prof Vergés said it was still early days for Operation Posidonia, but she hoped it would inspire people to get involved just as its sister seaweed restoration project Operation Crayweed did.

“Anybody who spends time in Port Stephens can help us by collecting seagrass shoots and as we expand to new sites, we will be looking for more people to help us,” she said.

“We also have a donations page – every donation makes a positive difference.

“Operation Crayweed received several hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations, so these are substantial projects to get off the ground.

“We look forward to developing philanthropic ties to support the future of Operation Posidonia.”

Unchaining the sea floor

A/Prof Vergés said it was important that Operation Posidonia had the twin aims of restoration of the endangered seagrass and the removal of the problem: traditional swing moorings.

“It’s difficult because moorings are owned by individuals and there is no strict regulation asking owners to have certain types of environmentally friendly designs,” she said.

“So, this project is partly about encouraging people to use a different mooring design that does not damage the seafloor.

“What we hope to do with this project is to show how this can lead to solutions and the recovery of lost habitats.

“We hope that will inspire mooring owners to become part of the solution and switch to an EFM.”

An EFM has no heavy chain and is usually made from a buoyant, synthetic material which hovers above the sea floor without drag.

Operation Posidonia’s “Look After Your Bottom” campaign aims to raise awareness about the issue.

‘Rewilding’ and climate change

Last month, A/Prof Vergés won UNSW Sydney’s inaugural Emerging Thought Leader Prize for her work in combining rigorous science with innovative public engagement techniques.

She grew up in Barcelona and spent her summers on the beautiful Balearic island of Mallorca snorkelling amongst the marine life in the Posidonia meadows of the Mediterranean.

“I fell in love with the sea and that’s what inspired me to study marine science,” she said.

“Restoration of underwater forests and seagrass meadows and the impact of climate change are the main areas of my work.”

A/Prof Vergés’ ultimate goal is to “rewild” our underwater forests and seagrass meadows and then climate-proof these habitats, because they are not only suffering from swing moorings and pollution – climate change is also having an impact.

“Rewilding” aims to restore functional ecosystems which have been lost.

“Potentially, the only way to future-proof Posidonia australis will be to intervene and to combine restoration with some assisted evolution approaches, to give the species the best chance to survive in a world that is changing very, very fast,” she said.

“In the marine environment, we are already seeing the impacts of climate change in a major way. Fishers are now catching species that used to be found in warmer waters, and we also have species and entire habitats that are disappearing.

“For example, 95 per cent of Tasmania’s giant kelp forests have disappeared – and that is because of climate change.”

Operation Posidonia has an ongoing grant from the NSW Environmental Trust program for Restoration and Rehabilitation.

This article was originally published by the UNSW Newsroom.